VC is a tool, not a religion

May 17, 2023

On this page

- Day 1 – We started bootstrapping, then changed our minds

- Raising money got intoxicating

- What happened next – The PostHog dark ages / turns out board meetings are very important!

- How to start focusing on revenue in the first place

- We have product-market fit, time to raise more money?

- Developer math

- So what should you take from this?

We raised over $27,000,000 then realized we should be growing out of our own revenue instead.

Day 1 – We started bootstrapping, then changed our minds

Fresh-faced, but not carefree – in the early days, when it was just my cofounder Tim and I, we used to work out of cafés and we were bootstrapped.

A few months in, we had a discussion on what we wanted out of life. Pro tip: do this before you start working with someone else. Luckily we were on the same page. We decided it was more stressful to bootstrap than to raise VC.

Why?

No money coming in meant we had to be exceptionally careful about spending anything.

We would spend years rebuilding to the same salaries we'd just left behind, but with added downside risk of not finding product-market fit.

A slower pace felt boring – it would be more engaging to own a smaller slice of a bigger pie. We wanted to work on something we'd enjoy.

The Y Combinator application was coming up, so we went for it. We got in.

Raising money got intoxicating

We raised a seed round fairly painfully (March 2020...). Then a Series A super quickly (a month later), then a B super-duper quickly (about 6 months later, and announced way after it happened).

Raising money, especially coming into 2021, felt self-fulfilling. It felt like you're either the type of company that raises a ton, or one that struggles. So we'd better keep raising. This was the hype loop we felt was happening:

- Founder: "Check it out, we raised tons of money!"

- VC: "Whoah, that's some compelling social proof! You're now on our radar."

- Users: "We should pick this technology since they're featured in TechCrunch with a huge funding round!"

- Founder: "We should keep raising. If we can raise the next round right now, not doing that feels stupid."

- VC: "Interest rates are low... let's do it."

- Go back to step 1 (until founder raises too much, has big unwieldy team and no product-market fit, with high burn, has to fire people and will struggle to raise again)

What happened next – The PostHog dark ages / turns out board meetings are very important!

Things got a bit messy.

We'd hired quite a bit. We didn't really have revenue but didn't really care about that, yet. We did have lots of users.

At the same time:

- Customers wanted a paid version of the product (asking for extra features or for us to host the product for them).

- Tons of the world's best investors were trying to talk to us.

- My daughter got cancer (she's now doing well, thankfully).

I wanted to keep working, but it meant I had to look after my daughter. I felt that if I tried to sell and fundraise, I'd do both badly.

We figured it was an existential problem not to have revenue, and that it'd be easier to figure it out now instead of when we're bigger.

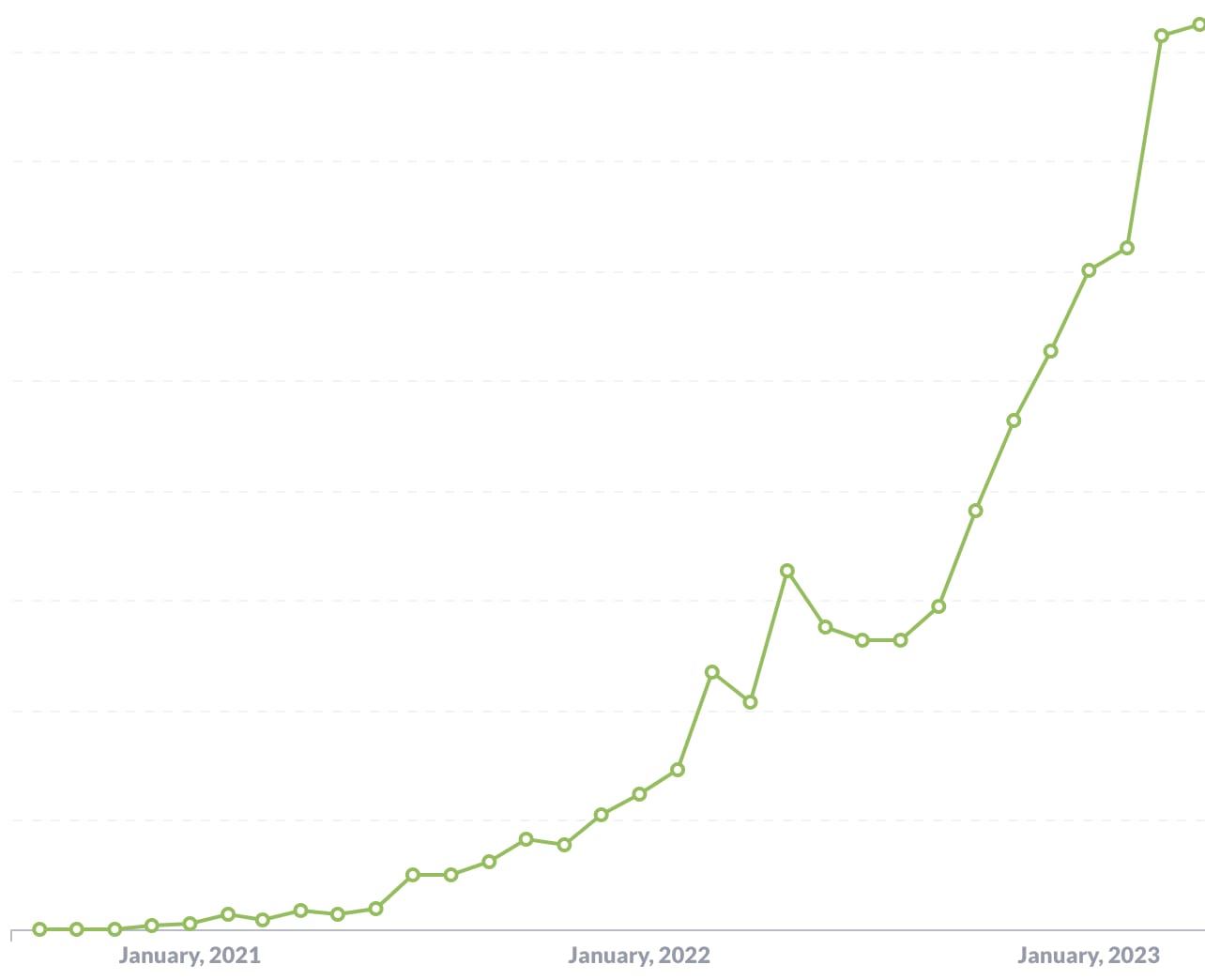

I couldn't be more glad that's what we picked. Results:

How to start focusing on revenue in the first place

This we nailed.

First, when we launched the free open-source product, we made clear from the outset that we would have a paid offering. We did this by explaining our different offerings on our pricing page.

Once we started getting regular demand for the paid product, and after feeling that the open-source product was building a big community who were getting value from it, we decided to focus on revenue.

We quickly set the goal of '5 reference customers' for the entire organization. We tracked the things each potential customer had in common – very specific things like "do they have product-market fit?" / "do they have a data warehouse?" / "have they used our free product before?".

Quickly we could spot the kind of deals that would close and the kind that wouldn't – it was really useful tracking both the deals that closed and the ones that dragged on.

There were three surprising lessons we had during this phase:

Charging customers for a product led to more usage. Early paying customers were more demanding of quality. When we fixed quality issues, our free and paid products both accelerated.

How important it is to track your anti-Ideal Customer Profile. Don't just monitor deals that close, but track those that are dragging on – what do they have in common?

How quickly we went from getting the first 5 paying customers, to 100.

We have product-market fit, time to raise more money?

Many companies do this. The reason is pretty simple – if you grow by hiring salespeople, you can use venture capital to hire faster than you could otherwise afford.

We took the stance that we should get to $10m in recurring revenue, and then (could) go nuts. This would mean we could raise capital easily, on great terms, and we'd have very solid product-market fit.

However, now that figure is getting close – we're no longer convinced this is the right thing to do. The way we grow is pretty simple:

- Make the existing products we have work better

- Add extra products to the platform

- Content marketing (👋)

Normal companies probably should raise venture capital, since most grow by hiring a big sales team whilst the product tries to keep up. PostHog's main growth lever is shipping.

Developer math

So, if we grow by shipping, and we want to grow as fast as possible – we need to be able to ship as fast as possible.

Adding developers is an intense process for us – particularly as we have found we work best with experienced people. We think it's the nature of an all-remote company with a wide product – we need people that thrive in autonomy, and those folk normally don't need as much coaching.

So, if we add lots of people, will we ship faster?

To a certain extent.

- Every hire involves dozens of interviews

- New technical hires require onboarding

Since our revenue is growing fast, we could triple or more our team next year, just from revenue growth. Hiring more than that feels like our developers won't really be writing code. So, we don't think a huge fundraise is the right thing to do.

So what should you take from this?

For us, I think we probably will fundraise again. However, our goals may be different to the norm – like just making sure we have more working capital so we can stay long term focused, to provide employee secondaries, or to get the ideal board member into the company.

Venture Capital is a tool, not a religion. Don't blindly follow what you hear others are doing on TechCrunch.

Instead, have a clear fundraising purpose. If it's to accelerate growth, great. Just ask yourself if it will actually help achieve that based on how your company is growing.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Product for Engineers

Helping engineers and founders flex their product muscles

We'll share your email with Substack